[post by Nancy Martin]

Hug a Vet for Veterans Day!

How to celebrate Veterans Day? The department of Veterans Affairs website lists the purpose of Veterans Day:

A celebration to honor America’s veterans for their patriotism, love of country, and willingness to serve and sacrifice for the common good.

Lots of communities hold parades and I encourage you to attend those, but don’t forget to hug your favorite veteran and tell them thank you. When I’m out and see someone in a military uniform, I make a point of going up to them and saying “Thank you for your service.” A simple sentiment, but something they appreciate hearing. I usually do the same thing for those wearing a cap or jacket that identifies them as veterans. If you are at a parade and see someone standing taller and saluting rather than putting their hand over their heart as flag passes, they are likely a veteran – thank them also.

When I think of someone celebrating Veterans Day right, Mary and Maureen come immediately to mind. In November 2005, a patriotic veteran, my father-in-law Frank Wayne Martin, who served the common good in and out of military, was in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit at Yale Hospital. Mary and Maureen made that Veterans Day special and memorable for him.

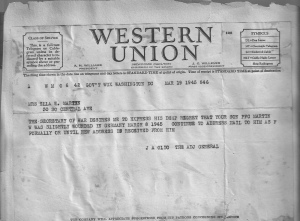

Wayne’s congestive heart failure had reached a critical point, despite getting a pacemaker the previous summer. In early November, the first surgeon who evaluated Wayne refused to operate, saying “He wouldn’t make it off the table alive.”

We asked for and received a second opinion. Dr. Cary Passik examined Wayne, heard some of his WWII stories, including the one where the 5th Rangers nickname for Wayne was “Survivor Martin.” The doctor knew a key to living and living well was Wayne’s survivor spirit, which was still very much intact. Dr. Passik also thought the operation was very risky, but felt if Wayne survived it would restore him to a decent quality of life. The surgeon, after explaining the risks and complications – not sugar-coating the hard work of post-surgery rehabilitation – asked Wayne if he wanted the risky operation.

He unhesitatingly answered “Sure, what the heck. It beats the alternative. Let’s do it!” The heart surgery was scheduled a week out on November 15, triple bypass and a heart valve replacement.

I had been updating his many friends on his condition. Two of them, Mary and Maureen, are tour guides at the United States Military Academy at West Point. They drove two hours each way to celebrate Veterans Day with a veteran who needed their support. They certainly honored the spirit of Veterans Day as they visited him. They brought flowers, candy and a little stuffed animal, an Army mule. Most importantly, they brought themselves – the gift of presence.

Wayne’s prognosis was bleak that Veterans Day, but he still had that ‘survivor spirit’ that helped him survive nine months in combat in a job doing a job with an official two-day life expectancy. Their visit helped buoy his spirits. We joked that both Wayne and General Patton could be stubborn as mules. Wayne was still following General Patton’s advice that “humor is important to survival,” and the laughter we shared was tonic for him. He joked that he was too stubborn to die during the war.

Wayne’s ’West Point girl friends’ had met him when he took their campus tour. They perceptively recognized he was walking history and soon discovered he had been a forward observer for General Patton in Europe. Wayne liked to visit the Academy frequently and eat at Thayer Hall. He often dropped by to say hi to his friends and share his latest war story write-up over an ice cream at a shop near campus.

Like so many of his friends and family, Mary and Maureen’s fascination of his WWII stories grew over time. They were among the chorus encouraging him to write a book. That Veterans Day, Wayne finally decided, at age 82, to consider himself retired from engineering and agree to work on publishing a memoir book. He already had a rough collection of his stories, with the working title Never a Dull Moment.

I am proud to say that the Daughters of the US Army gift shop at West Point sells Wayne’s book, Patton’s Lucky Scout. I know Wayne was pleased at that fact and I would like to think his mentor approves also. After all, the running joke is General Patton’s statue still roams around the academy grounds . . . looking for the library.

Ironically, November 11, Veteran’s Day, is also General George S. Patton’s birthday.

I still have and treasure that little mule. As Mary and Maureen went out of their way to do for Wayne, I encourage everyone who loves freedom to thank a veteran. Use Veterans Day as a good excuse to hug your favorite veteran and thank all who serve.